On a dismal, murky, drizzling February morning in 1949, I joined a queue of very nervous, apprehensive male teenagers wearing only their underpants, waiting to be medically examined by army doctors in a cold Reading assembly hall. We were all due to serve our eighteen months National Service.

Unlike the others I was neither nervous nor apprehensive for I had only recently left Lancing College, a confident, arrogant snob with the undeniable knowledge that public school boys were reliable, superior human beings capable of overcoming any set back. Experiencing life as a soldier for a while could only benefit my future acting career which I was determined to follow. I also secretly knew that I was the son of a diplomat and had therefore inherited the advantageous talent of psychological manipulation which meant that I was obviously officer material and, therefore, looked forward to donning a smart uniform which would attract female women. The testosterone was rising.

On top of that, my mother, forever guilt ridden for burdening me with the pretence that I wasn’t really who I was, attempted to give me even more confidence about going into the army by showing me old family photographs of the 1914 war.

Passed A1, I presented myself at the recruits’ barracks in Aldershot a few weeks later, immediately applied for a commission in the Intelligence Corps ( I was, after all bi-lingual ) and was duly sent for a second medical examination to make sure that I was fit enough to cope with the rigours of the Officer Cadets Training Unit.

I again proved to be extremely healthy until I came under the scrutiny of the ophthalmologist who asked me to read off the letters on the usual board without my glasses.

'I can’t actually see the board sir,' I said, squinting to make sense of the white blur on a distant wall.

'What’s that ? What ?' said he, stubbing out his cigarette. He picked up my spectacles, studied the lenses and turned to me stupefied. 'We can’t have individuals like you wandering about sightless on the battlefield. A serious error has been made. I’m afraid I must recommend that you be discharged from the army forthwith.

I was removed from the recruit's barracks to the quarters of a Holding Platoon where I found myself among fierce Glaswegians, cocky Cockneys, tough Geordies and aggressive Scouses who were all being honourably discharged because they either had flat feet, asthma or were so simple minded that the military didn’t want them.

While awaiting the discharge papers, we were given menial duties to keep our spirits up - cleaning latrines, collecting refuse, making officers’ beds - and when we went to the canteen for meals, we seemed to be regarded as lepers by the healthier soldiers.

Ordered back to barracks early every evening, I was quite content to lie on my bunk and lose myself in a book. This irritated the others who had no idea how to occupy their minds, most of whom were unsettled at having been rejected by the army which would have offered them a better life than the one they led back home. However, one illiterate character, fascinated by the joy I was clearly getting from sticking my nose in amongst the hundreds of pages he did not understand, asked if I could read him a story.

'I can read you the whole book,' I said, 'A chapter a night, if you want.'

And I did.

Every night, before lights out, a score of miserable characters sat on their beds and on the floor around me as I read them Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Even better, at tea time in the canteen, I started plonking the piano and got them to sing along.

The adrenalin rush when I did either of these things was very gratifying..I was performing of course, I was on stage with a captive audience dying for entertainment. My disappointment at not becoming an officer was replaced by the gratifying thought that a year and a half of my life would not be wasted. I would now go to RADA ( Royal Academy of Dramatic Art ) instead of OCTU ( Officer Cadets Training Unit ). My army career had lasted exactly three weeks.

My return home was not that of a welcomed military hero.

My non-father, believing he was rid of me for quite a while, was exasperated by the fact that I was once more foot loose and fancy free and instantly dismissed any ideas I had about acting. I would instead, he informed me, serve a sensible apprenticeship as a pork butcher in a salami factory abroad.

My mother again begged me not to rock the boat, not to argue, not to oppose him as it would have been reasonable to do had I been his real son. .....and I realized I was doomed.

The scene is the country kitchen of the Thames side house known as Weir Pool, in Pangbourne. Berkshire. October 1948.

Four characters are seated round the table finishing lunch. Eddy (54) the head of the house. Simone (44) his wife. Pierre (25) her lover. Drew (18) her illegitimate son.

Eddy knows that Drew is not his son but does not know that Drew knows, nor that Pierre also knows and is his wife’s lover.

Simone, of course, knows that Drew is not Eddy’s son and that Pierre is her lover.

Pierre knows everything about everybody.

Drew also knows everything about everybody and has the awesome responsibility of making sure that Eddy does not realize this.

The four are discussing ‘Huis Clos’ ( No Exit ) the play by Jean Paul Sartre which has been in the news because of a recent stage production.

The plot revolves around three deceased people punished by being locked in a room together for eternity. It is dangerous to bring up such a subject for it concern deception, secrets and lies, actions perpetrated daily, by Simone, Pierre and Drew, Eddy being the innocent victim of such duplicity.

‘It’s true. Hell is other people ‘ Simone says referring to a famous line from the play and looking pointedly at Eddy.

'You’re telling me!' Eddy replies, pointedly looking back at her.

He gets up and leaves the room...

Pierre makes a face at Simone suggesting she has gone too far. Drew sighs deeply and closes his eyes. There is hate in the house and the atmosphere is becoming poisonous.

Shortly after Drew was born and Eddy learned of what can only be called ‘the tragedy’, it was agreed between husband and wife that the boy would be brought up as their son and that the truth would never ever be mentioned again but, from that day on, the couple have seldom let the matter rest. Fortunately Pierre, a permanent guest in the house, acts as a buffer between the inharmonious pair and, more often than not, pretends to take Eddy’s side to calm things down. 'When you’re not here', he tells Drew, 'they manage to forget the past and are reasonably content.'

So Drew is a constant reminder of his mother’s misconduct and realizes that, since leaving school, he has been a pariah at a loose end in the house. Soon, however, he will be called up to do his 18 months National Service which he is looking forward to.

The army cannot be worse than the oppressive family atmosphere.

Simone and Eddy on a rare occasion when they seem reasonably contented

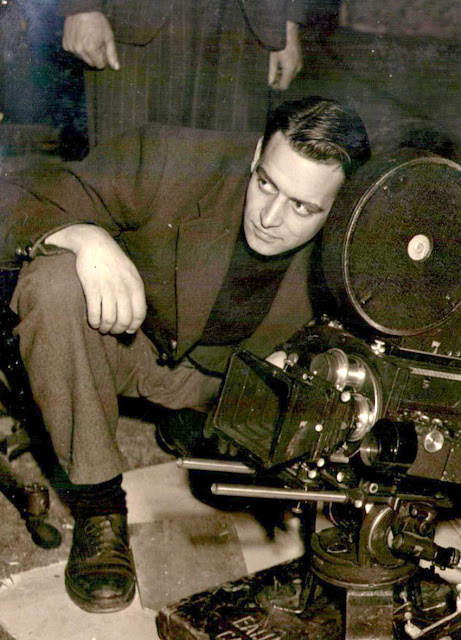

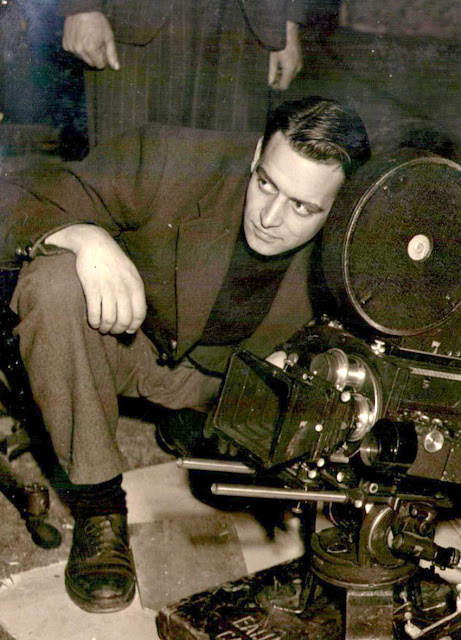

Pierre on the film set of 'A Matter of Life and Death''

Pierre on the film set of 'A Matter of Life and Death''

Back in 1968 my literary agent, a fervently ambitious man, told me it was time I produced a worthwhile novel. Up till then I had been responsible for a series of cartoons, written a number of humorous thrillers, published several non fiction books, worked in television and compiled a serious dictionary of dates. He couldn’t pigeon-hole me as a specialized author and agents like to pigeon-hole their authors because it makes their life easier - he’s into science fiction, history, romance, haute cuisine, eroticism - that type of thing.

'Id have to find at least a year of no worries,' I pointed out. 'I have a wife, two young sons and a mortgage to maintain.'

'Give them all up,' he said. 'Uproot! Go abroad somewhere cheap and write about the resulting domestic trauma. That’ll be a good subject. You’re not getting any younger.'

I was thirty eight.

I did what I was told. I sold the house in Somerset where we were all then living and went to Spain taking the family with me.

It was adventurous, brave and foolhardy.

We settled in Frigiliana, a remote Andalusian village up in the mountains six kilometres from the coastal town of Nerja, east of Malaga, the sort of place creative people dream about, no telephones, no television, the post delivered once a week by the fishmonger on a mule.

The pueblo was a maze of narrow streets flanked by ancient whitewashed houses with balconies hung heavy with geraniums in multicoloured pots, every doorway open and nearly every threshold occupied by an elderly widow who would wear black till her own death and young girls squinting at their lacework. It was peasant from the dung between the cobblestones to the earthy smell of heated olive oil and chorizo sausage coming from the primitive kitchens.

I loved it all because the geography of the area and the blue Mediterranean reminded me of the Côte d’Azur, Malaga not unlike Nice, Frigiliana and Nerja not unlike Cagnes and Cagnes-sur-Mer where I had enjoyed early childhood days, added to which I had perhaps inherited a deep affection for Spain through my mother’s genes, for when she returned from a visit there before I was born she had surrounded herself with Spanish furniture, named our London house 'Alba' (dawn) had gone over the top with wrought iron entrance gates and made me up as a bullfighter for my first fancy dress party.

To start with we rented a place, then bought a ruin and renovated that. It took more than a year during which time I did not put pen to paper and when I finally did, demanding peace and solitude, my wife and sons got bored, moved down to more lively Nerja and the marriage broke up.

We had been married fifteen years, had never argued, so that the inevitable disagreements had been swept under the carpet for too long and all burst out spiritedly with the help of wine at 9 pesetas a bottle leading to a reasonably amicable divorce - fantastic material for a domestic trauma best seller.

Wandering the streets and bars of other local towns alone in search of inspiration, I later chanced upon a fiery foot-stamping mad-as-a-sombrero señorita from Granada. She was seventeen years younger than me, I fell in love and eventually married her.

I produced not one but seven worthwhile novels after that and, with her help, a daughter, Melissa, who is responsible for starting this Blog.

André as a bullfighter aged 8.

I will not dwell on my English boarding school trials which followed my two intriguing terms as the only boy in a girls’ school, for too many autobiographies have been written by sensitive authors about such academies ruining their lives. Suffice it to say that both Claremont Preparatory and Lancing College to which I was sent, had teaching staff whose only aim in life was to prepare their pupils to become Field Marshals in command of the Indian army, Archbishops of Cantebury or first class cricketers. Latin, Greek and Ancient History were indifferently taught by aged, bored and worn out masters, the younger, keener and more energetic staff were all at war.

Claremont School, five miles from Pangbourne, was chosen as it was close enough for my mother to believe I could walk home should something terrible happen - like the Germans invading the British Isles and all forms of transport being paralysed. It might as well have been a thousand miles away as far as I was concerned.

It was forbidden to venture beyond the school boundaries so we never made contact with other human beings. It was an alien world to me with not a girl in sight and only one friendly female, the matron, who had enormous teeth and a mouth large enough to contain them.

Being sent away from home did, however, reveal a surprising fact. I had never really thought about the relationship I had with my parents, I was too young to analyse such things and they were always there, but when I experienced the sudden separation I became aware of my mother’s love for me, seldom demonstrated, and my father’s apparent indifference to my existence except as a possible future managing director of the family firm.

When my mother first dropped me off on the doorstep of a building that looked as welcoming as any Dickensian institution, I naturally cried my eyes out.

When she waved at me from the back window of the taxi that drove her away and I saw that, she too, was in tears, I was quite shaken by this unexpected evidence of a hidden affection. During the term I received letters from her telling me how much she missed me and I started marking off the days in my diary till I would get home for the holidays and be hugged and kissed and loved as never before.

But this did not happen as expected.

I had to wait till we were alone for her to display any form of affection, and for the first time noticed that she was even more distant in the presence of my father

There was a reason for this which I recounted five posts back, but I was not to know it for another two years.

So the only joy I experienced in that hell-hole was my being cast as King Lear in an end of term production of the tragedy which allowed me to gaze in a mirror entranced at myself as the old lunatic monarch with white hair and white beard.

Slipping into another persona was fantastic. Hi diddle dee dee, it was going to be an actor’s life for me

At Lancing the teaching was decidedly better, the masters tried their best to get me interested in their particular subjects, but I lacked concentration except for play reading or any activities connected with the dramatic society. I was cast as an interpreter in a French play, astounding everyone with my perfect command of the language, and when I played Julius Caesar in toga and laurel leaves about my head, I knew for certain that the moment my school days were over I would go to drama school, then a year or two in repertory, then the Royal Shakespeare Company.

It didn’t quite work out that way...

King Lear - Sir Ian McKellen.

Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

December has always been a happy month for me as Christmas is heralded by my birthday on the 12th, Presents. therefore, could be anticipated, and though people around me threatened gloom in 1939 because of the war, I do not remember being particularly perturbed. Apart from soldiers being trained to build pontoon bridges across the Thames a little further down from the weir, our guest refugees complaining about clothes rationing and the sudden disappearance of bananas, the early months of the conflict made little impression on me. My mother gave up trying to teach me anything and passed that duty onto Honorine our new cook who sat me down in the corner of the kitchen and saw to it that I did a few arithmetic problems and read stories aloud to her from an English book, none of which she understood. She was a roly-poly woman with an infectious laugh and as lewd a sense of humour as Maman in Nice. Within a week of settling in one of the attic rooms and taking over command of the kitchen she was shocked to find out that I did not know the facts of life and promptly enlightened me on the subject in great detail while stuffing a chicken. 'If men had more control of their little willies there wouldn’t be any wars.' she said.

One evening in December, when we were sitting by the drawing room fire, my father read out an article in his newspaper about how the German warship Admiral Graf Spee had been scuttled in Montevideo harbour.

I had never heard of Montevideo let alone Uruguay and this quite shocked him. Questioning me about other capitals of the world, he realized that my knowledge of geography was negligible and that I was also remarkably ignorant on most other subjects.

Seeking advice from the headmistress of my sister’s school, she informed him that, as so many city children were being evacuated to the country because of possible air raids, she was thinking of taking in a small number of boy pupils from good families to alleviate the situation, and suggested I attend her school as a sort of guinea pig to see how things worked out?

So, at the start of the following term, I joined my sister at Miss Hatfield’s, the only boy among forty two girls, and the only pupil to leave the seat up after using the lavatory..

I cannot deny that I enjoyed my short time there..

I knew what girls liked and disliked because my sister was one, but my knowledge of why they lied, how they manipulated others, pretended innocence and instinctively knew how to twist males of any age round their little fingers was greatly enhanced. Though I didn’t have any particularly attractive attributes, as the only male I was unique and so prey to female curiosity. Brother-less Lucy, for example, paid me sixpence to show her something she had never seen before...

Unfortunately I became infatuated with Sybil, my age, who had long flaxen hair, green eyes and would have been pretty but for an upturned nose that suggested she thought herself superior to others. It wasn’t that she was a snob exactly, but she did let me know that I wouldn’t be invited to her birthday party during the holidays because we were ‘trade’, worse, in ‘catering’ and 'foreign'. I never met her parents who must have been responsible for this attitude and anyway gave up on her when she told me she preferred horses to humans.

Apart from English, arithmetic, geography and history, I was taught how to knit and crochet and quite liked playing netball and rounders.

When I invited Jane, Brenda and Carol round to the house one Sunday afternoon to play with me and their dolls, my father decided I should be sent to a boy’s boarding school as soon as possible.

It was the kiss of death.

The war with Germany was declared on September 3rd 1939 but nothing much disturbed the pleasant life I was leading till the Spring of 1940 when things got a bit more hairy with convoys of army lorries and Bren gun carriers roaring past the house and platoons of British, Canadian and Australian soldiers marching down the street on their way to a newly established training camp outside the village.

One evening, my father came home with a tin helmet announcing that he would have to stay at the office two nights a week to fire watch. Within days London was targeted by the Luftwaffe and, shortly after, our peaceful, orderly, riverside house was invaded by eight agitated refugees from the bombs, all of them family friends who originally hailed from the South of France and were in the catering business. One of them was the part owner of Randall & Aubin, a famous delicatessen in Brewer Street, which still carries the same name but is now a fashionable caviare bar, another was the Chef of the Dorchester Hotel, another was the manager of the Café Royal in Regent Street.

During the first week of June, allied troops were evacuated from Dunkirk, ten days later the Germans entered Paris, French delegates accepted terms of an armistice and hostilities ceased in France. The atmosphere in the house became desperate. No one knew what was happening to relatives and friends across the Channel, nor what horrors the future might bring and, to add insult to injury, some ill informed villager painted a swastika on our garden wall believing that we were German collaborators. This was so upsetting that everyone endeavoured to speak only English, an effort which lasted about two days, my sister was henceforth called ‘Reggie’ and myself ‘Andrew’ which was soon shortened to ‘Drew’. One week-end our now resident Chef de Cuisine indulged everyone in an epicurean feast with the help of left-overs from the fridges of the Dorchester and luxury products from the stockroom of my father's factory. Everyone believed it might be our ‘Last Supper’. My sister and I lay the long table in the dining room for the much discussed meal to come, my father uncorked bottles of superlative wines, and in the kitchen eggs were mercilessly beaten, cream whisked, saucepans spat and spluttered, orange and blue flames shot dangerously up to the ceiling from overworked copper pans and the whole house smelt delicious.

Among the dishes served was a massive central bowl of caviare, several terrines of foie gras, lobsters, Turtle Soup, Truite Meuniere, pheasant, Aberdeen Angus roast beef, a variety of English cheeses, Peche Melba laced with Creme Chantilly all served with Krug champagne, Bordeaux and Burgundy wines followed by coffee, Cognac Armagnac and Kummel. Too young to fully appreciate all that was on offer, I was force fed a bit of everything as I was thin and I might never come across anything quite as delectable again. We started eating at 2 pm, finished at 11 pm and the sweet white wine to which I took a liking resulted in me becoming very dewy eyed.

On reflection this little banquet was quite obscene considering most of our neighbours were managing on powdered eggs and toast, the attitude of the adults, however, was not only 'enjoy if you can - endure when you must.' but a way of defying the enemy. When everyone wiped their mouths and suppressed a rude burp at the end of each meal from then on, somebody round the table always stated with great satisfaction 'One more the Germans will not have !'.

Dewy eyed after the banquet.

Edyy Launay as a private in the French army with dog

Edyy Launay as a private in the French army with dog My mother perched on a wrecked German tank when she was made to visit the 1914 battlefields with her in-laws

My mother perched on a wrecked German tank when she was made to visit the 1914 battlefields with her in-laws